What Parts of Democracy in America to Read

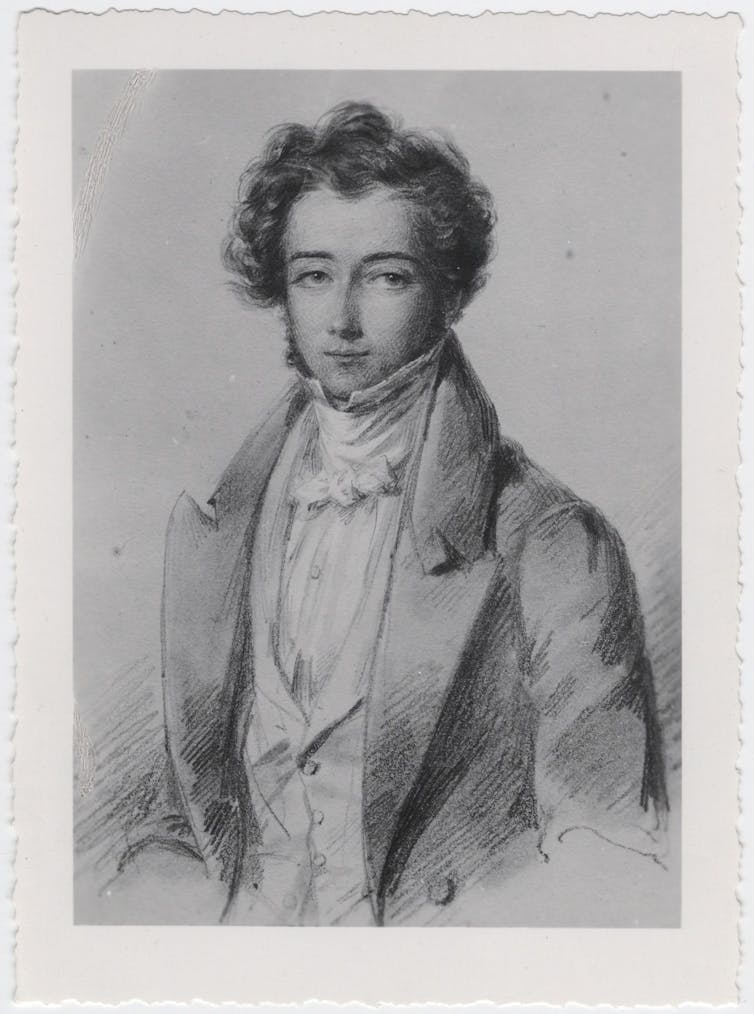

The following remarks on a famous work by Alexis de Tocqueville (1805 - 1859) were presented equally a lecture to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Scholars Program at the University of Sydney, 24th April, 2015.

Alexis de Tocqueville's four-volume Democracy in America (1835-1840) is commonly said to exist among the greatest works of nineteenth-century political writing. Its daring conjectures, elegant prose, formidable length and narrative complexity brand it a masterpiece, yet exactly those qualities have together ensured, through time, that opinions greatly differ about the roots of its greatness.

Some observers cautiously mine the text for its fresh insights on such perennial themes every bit liberty of the press, the tyranny of the bulk and ceremonious order; or they focus on such topics as why information technology is that modern democracies are vulnerable to 'commercial panics' and why they simultaneously value equality, reduce the threat of revolution and grow complacent. Some readers of the text treat its author as a 'classical liberal' who loved parliamentary regime and loathed the extremes of republic. More oft, the text is treated as a brilliant grand commentary on the decisive historical significance for old Europe of the rise of the new American republic, which was presently to become a world empire. Some observers, very often American, push this interpretation to the limit. They think of Democracy in America in most nationalist terms: for them, it is a lavish hymn to the Us, a commemoration of its emerging authority in the world, an ode to its 19th-century greatness and future 20th-century global say-so.

How should nosotros make sense of these conflicting interpretations? Each arguably suffers serious flaws, but at the outset it'south important to recognise that the act of reading past texts is always an exercise in selection. There are no 'truthful' and 'true-blue' readings of what others have written. Readers like to say that they take 'really grasped' the intended meanings of dead authors, whose texts belong to a context, only 'full disclosure' of that kind is forbidden to the living. Hemmed in by linguistic communication and horizons of time and infinite, reading is e'er a stylising of by reality. Just as walking is a pale fake of dancing, and dancing an exaggerated course of walking, so interpretations frame past realities. They are acts of narration. Acts of reading past texts are always time- and space-bound interpretations and, as one of my teachers Hans-Georg Gadamer liked to remark, all such interpretations of past texts plow out to be misinterpretations. That is why differences of interpretation are not only to exist expected merely, in gild to prevent any one of them condign dominant, to be welcomed, especially when they button beyond familiar horizons, towards 'wild' perspectives that force united states of america to rethink things that we have and then far taken for granted.

Democratic Literature

It is the spirit of 'wild reading' that infuses the post-obit notes on Tocqueville'due south 'classic' piece of work. When approached 1 hundred and 70 years after its first publication as a iv-volume prepare, Commonwealth in America teaches united states more than than a few things about the subject field of democracy. But what exactly tin can we learn from information technology? It may seem far-fetched, merely the first striking affair about the text is non just that it is the first-always lengthy analytic handling in any language of the subject of democracy just a treatment whose narrative grade both mirrors and amplifies ('mimics') the dynamic openness of its subject matter: a mode of life and a method of handling power Tocqueville repeatedly calls democracy. Republic in America is a democratic text. Hit is its openness, its willingness to entertain paradoxes and juggle opposites, its powerful sense of run a risk constructed from extensive field notes gathered by means of a yard adventure.

Information technology may not seem obvious, just this sense of adventure has everything to practice with the spirit of 'democracy'. Democracy in America brilliantly captures and mimics in literary form the growth of an open up, experimental society, a dynamic political order deeply aware of its ain originality. Its grasp of these qualities of democracy was undoubtedly nurtured by Tocqueville's peripatetic through the young American commonwealth. It opened his eyes, widened his horizons, and inverse his heed nigh democracy. In 1831, for nine short just activity-filled months, the 26-year-old young French aristocrat (1805-1859) travelled through the United States. Accompanied past his colleague and friend Gustave de Beaumont, he ventured almost everywhere. Similar a well-briefed tourist, he rode on steamboats (1 of which sunk), found himself trapped by blizzards, sampled the local cuisine, and slept crude in log cabins. He found time for enquiry and for rest, and for chat, despite his imperfect English, with useful or prominent Americans, among them John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson and Daniel Webster.

Setting out from New York, he travelled upstate to Buffalo, so through the frontier, every bit information technology was then called, to Michigan and Wisconsin. He sojourned ii weeks in Canada, from where he descended to Boston and Philadelphia and Baltimore. Next he went west, to Pittsburgh and Cincinatti; and then south to Nashville, Memphis, and New Orleans; then north through the south-eastern states to the capital, Washington; and at concluding back to New York, where he returned by packet to Le Havre, France. At the outset of his journey, in New York, where he sojourned from May 11th for some vi weeks, Tocqueville was openly hesitant nearly this bustling market social club whose arrangement of democratic regime was still in its infancy. 'Everything I see fails to excite my enthusiasm,' he wrote in his journal, 'considering I attribute more to the nature of things than to human will.'

Talk of the God-given nature of things appears from fourth dimension to time between the lines of Republic in America. Seemingly still under the influence of the political false starts of his native France, the 'nature of things' principle stands in some tension with its sense of adventure, with its feeling for the novelty of republic equally a transformative experience. But Tocqueville, the slightly built son of a count from Normandy - the Château Tocqueville still stands, within sight of the harbour of Cherbourg - was soon to change his heed about democracy. Sometime during his stay in Boston (7 September - three October, 1831), Tocqueville became a convert of the American way of life. He began to talk of 'a great democratic revolution' at present sweeping the world from its American heartlands. He was persuaded that 'the appearance of commonwealth equally a governing power in the earth'southward affairs, universal and irresistible, was at hand'. He became convinced that 'the time was coming' when commonwealth would triumph in Europe, every bit information technology was doing in America. The future was America. It was therefore imperative to sympathize its strengths and weaknesses, he thought. And and then, on Jan 12th 1832, just earlier boarding his packet for France, he sketched plans to bring to the French public a work nearly republic in America. 'If royalists could encounter the internal performance of this well-ordered commonwealth,' he wrote, 'the deep respect its people profess for their acquired rights, the power of those rights over crowds, the religion of law, the real and effective liberty people enjoy, the true dominion of the bulk, the easy and natural manner things proceed, they would realise that they apply a unmarried name to diverse forms of government which have nothing in mutual. Our republicans would experience that what we accept called the Republic was never more than than an unclassifiable monster…covered in claret and mud, clothed in the rages of antiquity's quarrels.'

Tocqueville'due south epiphany produced a string of boggling insights, also equally paradoxes. Consider his claim in Republic in America that the political form known equally democracy, all things considered, extinguishes the artful dimension of life. It produces no lasting works of art, no poetry, no fine literature. Defective a leisure class, he reasoned, the young American democracy cultivated people with applied minds. 'The linguistic communication, the dress, and the daily actions of men in democracies are repugnant to conceptions of the ideal', he wrote. The whole 'philosophical method' of democracy is pragmatic, centred on the effort of individuals to make sense of their world past harnessing their own individual agreement of things. Even in matters of religion, 'everyone shuts himself upwardly tightly inside himself and insists upon judging the world from there'.

The often-beautiful narrative prose, self-conscious reflection and fragmented 'open text' structure of Commonwealth in America contradicts this thesis. Democracy in America is arguably a corking piece of work of modern democratic literature, a highly engaging and thought-provoking text that markedly stands at correct angles to the tedious-witted scientific discipline of politics that is today dominant in the American academy, and elsewhere. The signal can exist put in a unlike way: Tocqueville positively contradicted himself. He failed to foresee the many ways in which the immature American republic, with its palpable ethos of equality with freedom manifested in simple trunk linguistic communication, tobacco-chewing customs and like shooting fish in a barrel manners, would give rise to self-consciously autonomous fine art and literature. Walt Whitman'south Leaves of Grass (1855), a celebration of the potential boundlessness of the American experiment with democracy and of the power of the poet to rupture conventional language springs to heed. Then also does the greatest of all nineteenth-century American novels, Hermann Melville'southward Moby-Dick (1851), a tale that warned against the hubris and self-devastation that awaits all those who deed as if the globe independent no boundaries, rules or moral limits. Tocqueville's Republic in America stands tall among these 'classics'. It is in fact their progenitor.

Contingency

Simply at that place'southward more to say about Democracy in America: much more, in fact. Democracy in America is a genuine breakthrough in the agreement of democracy as a unique political form, every bit a whole manner of life that is fundamentally transformative of people's sense of being in the world. Standing backside Tocqueville's fascination with democracy is his sensation of its profound function in shaping modern times by stirring upward people's sense of the contingency of things. The four-volume work is still regarded, justifiably, equally one of the great books nearly the subject, in no modest measure because at a crucial moment in the democratic experiment in America Tocqueville managed to put his finger on several sources of its dynamic energy. For Tocqueville, it is non simply capitalism and the law-enforcing territorial land that define modern times. The 'peachy democratic revolution' marks off modernity from the prior globe structured by what he repeatedly calls 'aristocracy'. Republic is a sui generis only seemingly irreversible feature of the modern age.

It is true in that location are more than a few hints that Tocqueville, backed past the belief that God stands in favour of commonwealth, is tempted by evolutionary thinking, of the kind (in much more secular form) that later gripped Fukuyama's grand generalisation of the 1776 revolution equally the beginning of the cease of history. Withal in contrast to Fukuyama and others, Tocqueville insisted there is no sure progress at the level of 'general development'. Tocqueville emphasises to his readers that democracy challenges settled ways of thinking and speaking and acting. Information technology reveals that humans are capable of transcending themselves. Really striking is Tocqueville's grasp of the style republic breaks down life'south certainties and spreads a lived sense of the mutability of the power relations through which people live their lives. For him, commonwealth is the twin of contingency.

The indicate is not often noted by readers of Tocqueville, but it is of fundamental importance when trying to come to terms with the 'spirit' of democracy. What we learn from Democracy in America is that democracy nudges and broadens people'southward horizons. It tutors their sense of pluralism. It prods them into taking greater responsibility for how, when and why they human action as they practise. Democracies encourage people's suspicions of power deemed 'natural'. Citizens come to learn that 'perpetual mutability' is their lot, and that they must keep an eye on power and its representatives because prevailing power relationships are not 'natural', merely upward for grabs. In other words, democracy promotes something of a Gestalt switch in the perception of power. The metaphysical idea of an objective, out-there-at-a-distance 'reality' is weakened; so, too, is the presumption that 'reality' is stubborn and somehow superior to power. The fabled distinction between what people tin encounter with their eyes and what they are told about the emperor's apparel breaks down. 'Reality', including the 'reality' promoted by the powerful, comes to be understood as always 'produced reality', a matter of estimation - and the power to seduce others into conformity past forcing particular interpretations of the world down others' throats.

The Spirit of Equality

What are the wellsprings of this shared sense of contingency? Why does democracy tend to interrupt certainties, impeach them, enable people to see that things could be other than they presently are? Tocqueville might accept been expected to say that considering periodic elections stir things upwardly they are the prime cause of the shared sense of the contingency of power relations. Not and then. Tocqueville actually thought that elections trigger herd instincts among citizens. He worried that 'faith in public stance' might well become 'a species of organized religion, and the majority its ministering prophet'. Though frequent elections 'keep guild in a feverish excitement and give a continual instability to public affairs', periodic elections are not seen past Tocqueville to be the core dynamic of commonwealth. The proximate cause of the 'spirit' of restlessness of democracy lies elsewhere: it is above all traceable to the way democracy unleashes struggles past groups and individuals for greater equality.

Tocqueville reminds us in Democracy in America that the core principle of commonwealth is the public commitment to equality among its citizens. The reminder seems lost these days on almost politicians, political parties and governments. Information technology's true that Tocqueville showed picayune interest in the finery of contested understandings of the meaning of equality. He was no dubiousness aware of Aristotle'south famous stardom betwixt 'numerical equality' and 'proportional equality', a class of equal treatment of others who are considered every bit equals in some or other of import respect, merely not others. Yet Tocqueville openly sided with Aristotle's view that democrats 'retrieve that as they are equal they ought to exist equal in all things'. Equality is for him not the equal right of citizens to be different. Equality is sameness (semblable). Proof of its allure was the way the new American commonwealth unleashed constant struggles confronting the various inequalities inherited from old Europe, thus proving that they were neither necessary nor desirable. Democracy, argued Tocqueville, spreads passion for the equalisation of power, property and status amongst people. They come to feel that electric current inequalities are purely contingent, and so potentially alterable by man activeness itself.

Tocqueville was fascinated by this trend towards equalisation. In the realm of law and government, he noted, everything tends to dispute and uncertainty. The grip of sentimental tradition, accented morality and religious faith in the power of the divine weakens. Growing numbers of Americans consequently harbour 'instinctive incredulity of the supernatural'. They also wait upon the power of politicians and governments with a jealous eye. Government structured by the good claret of monarchs is abomination. They are decumbent to suspect or curse those who wield power, and thereby they are impatient with capricious dominion. In the field of what Tocqueville calls 'political club', regime and its laws gradually lose their divinity and charm. They come to be regarded as just expedient for this or that purpose, and as properly based on the voluntary consent of citizens endowed with equal civil and political rights. The spell of absolute monarchy is forever broken. Political rights are extended gradually from the lucky privileged few to those who one time suffered discrimination; and government policies and laws are subject constantly to public grumbling, legal challenges and alteration.

Thanks to democracy, something like happens in the field of social life, or then Tocqueville proposed. The American democracy is subject to a permanent 'social revolution'. Himself a self-confessed sentimental believer in the sometime patriarchal principle that 'the sources of a wife's happiness are in the home of her husband', Tocqueville nevertheless pointed to a profound modify in the relationship between the sexes in American club. Democracy gradually destroys or modifies 'that nifty inequality of homo and adult female, which has appeared hitherto to exist rooted eternally in nature'. The more general point he wanted to make is this: under autonomous conditions, people's definitions of social life equally 'natural' or 'taken for granted' are gradually replaced by cocky-consciously chosen arrangements that favour equality as sameness.

Commonwealth speeds upwardly the 'de-naturing' of social life. Information technology becomes discipline to something like a permanent democratisation. This is how: if certain social groups defend their privileges, of belongings or income, for case, then force per unit area grows for extending those privileges to other social groups. 'And why not?', the protagonists of equality ask, adding in the same breath: 'Why should the privileged exist treated every bit if they were different, or meliorate?' Subsequently each new practical concession to the principle of equality, new demands from those who are socially excluded force nonetheless farther concessions from the privileged. Eventually the point is reached where the social privileges enjoyed by a few are re-distributed, in the grade of universal social entitlements.

That at to the lowest degree was the theory. On the basis of his travels and observations, Tocqueville predicted that American republic would in futurity have to confront a central dilemma. Put at its simplest, information technology was this: if privileged Americans endeavour, in the name of such-and-such a principle, to restrict social and political privileges to a few, then their opponents will be tempted to organise themselves, for the purpose of pointing out that such-and-such privileges are past no means 'natural', or God-given, and are therefore an open embarrassment to democracy. Democratic mechanisms, said Tocqueville, stimulate a passion for social and political equality that they cannot hands satisfy. He idea in that location was much truth in the view of Jean-Jacques Rousseau that democratic perfection is reserved for the deities. The earthly struggle for equalisation is never fully attainable. Information technology is e'er unfinished. Democracy lives forever in the future. There is no such thing as a pure republic and there never volition be a pure democracy. Democracy (as Jacques Derrida later put things) is always to come up. 'This complete equality', wrotes Tocqueville, 'slips from the easily of the people at the very moment when they think they have grasped it and flies, equally Pascal says, an eternal flight'.

The less powerful ranks of society, including those without the vote, are particularly caught in the grip of this levelling dynamic, or so Tocqueville thought. Irritated by the fact of their subordination, agitated by the possibility of overcoming their condition, they rather hands grow frustrated by the uncertainty of achieving equality. Their initial enthusiasm and promise give way to disappointment, merely at some point the frustration they feel renews their delivery to the struggle for equality. This 'perpetual movement of social club' fills the world of American commonwealth with the questioning of absolutes, with radical scepticism virtually inequality, and with an impatient love of experimentation, with new ways of doing things, for the sake of equality. America found itself caught upward in a democratic maelstrom. Zip is certain or inviolable, except the passionate, boundless struggle for social and political equality. 'No sooner do you fix foot upon American soil then you are stunned by a type of tumult', reported Tocqueville, stung by the same excitement. 'A confused clamour is heard everywhere, and a thousand voices simultaneously demand the satisfaction of their social needs. Everything is in motion around you', he continued. 'Here the people of one town commune are meeting to make up one's mind upon the building of a church; there the election of a representative is taking place; a trivial further on, the delegates of a district are hastening to town in order to consult about some local improvements; elsewhere, the labourers of a village quit their ploughs to deliberate upon a road or public school project.' He concluded: 'Citizens call meetings for the sole purpose of declaring their disapprobation of the behave of authorities; while in other assemblies citizens salute the authorities of the day equally the fathers of their country, or class societies which regard drunkenness every bit the main cause of the evils of the state, and solemnly pledge themselves to the principle of temperance.'

Civil Society

Tocqueville was certainly impressed by 'civil society' (société civile). He was not the first to apply the term in its modern sense (run across my earliest works Democracy and Civil Club and Civil Society and the State), just he did observe the new American republic brimming with many different forms of ceremonious association, and he therefore pondered their importance for consolidating democracy. Tocqueville was the first political writer to bring together the newly-invented modern agreement of civil society with the erstwhile Greek category of democracy; and he was the first to say that a salubrious commonwealth makes room for ceremonious associations that function as schools of public spirit, permanently open to all, within which citizens go acquainted with others, learn their rights and duties equally equals, and press dwelling their concerns, sometimes in opposition to regime, so preventing the tyranny of minorities by herd-similar majorities through the ballot box. He noted that these civil associations were small-calibration affairs, and yet, inside their confines, he emphasised how individual citizens regularly 'socialise' themselves past raising their concerns across their selfish, tetchy, narrowly private goals. Through their participation in ceremonious associations, they come to feel themselves to be citizens. They describe the conclusion that in order to obtain others' back up, they must often lend them their co-operation, every bit equals.

Tocqueville'south account of democracy in America shows, at a poignant moment in the nineteenth century, merely how pop thinking had become self-conscious of the novelty of civil society under democratic atmospheric condition. Tocqueville called upon his readers to understand democracy as a brand new blazon of cocky-regime defined not just by elections, parties and government by representatives, but also by the extensive utilise of civil club institutions that preclude political despotism by placing a limit, in the name of equality, upon the telescopic and power of government itself. Tocqueville also pointed out that these ceremonious associations had radical social implications. The 'smashing autonomous revolution' that was underway in America showed that information technology was the enemy of taken-for-granted privileges in all spheres of life. Under autonomous conditions, ceremonious society never stands still. It is a sphere of restlessness, civic agitation, refusals to cooperate, struggles for improved atmospheric condition, the incubator of visions of a more than equal society.

Pathologies of Commonwealth

Tocqueville's Democracy in America is worth reading for yet 1 more reason: it is the commencement-always analysis of commonwealth to dissect democracy's pathologies, and to do so in a manner that remained basically loyal to the spirit and substance of republic as a normative ideal. Readers of Democracy in America often brush aside this point. While they admit that Tocqueville was well aware that republic is prone to self-contradiction and self-destruction, they note that he tended to exaggerate the momentum and geographic extent of the decorated levelling procedure that was underway in America. According to this view, Tocqueville, who was blessed with a remarkable sixth sense of probing the difference betwixt appearances and realities, sometimes, when looking at life in the The states, swallowed whole its own best self-image.

He wasn't the simply nineteenth-century company to be overjoyed past the new republic. Consider the Italian fashion of visiting the new democratic republic, to run across what it was like. 'Hurrah to y'all, oh great Land!', wrote i traveller, shortly later Tocqueville had published his nifty work. 'The Usa is a free land, substantially because its sons drink together the milk of respect for each others' opinions…this is what makes them cute, and their air more easily breathable for united states who are thirsty for liberty from old Europe, where the liberties we have gained with and then much claret and pain have for the nigh function been suffocated by our mutual intolerance.' Some other Italian traveller expressed similar excitement. 'Ah, this is the democracy that I dear, that I dream of and yearn for', he wrote, contrasting it with the 'presumption and snobbishness' guarded back abode past the 'people of high rank'. The same company was struck by the way American citizens casually wore caps and hats, how they spurned moustaches, chewed tobacco, and liked to chew the fat, hands in pockets. 'Uncomplicated people, simple piece of furniture, simple greetings', he wrote, adding that Americans 'extend you their manus, inquire yous what you need, and rapidly respond.' Withal another visitor brimmed with exuberance. 'There is no lying by officials. Truth, e'er truth. No prejudices, no ruby tape. From every street corner come the cries of a people intoxicated with hope and immortal charity: "Forward! Forward!"'. He added an immodest prediction: 'Simply every bit Rome impressed the seal of its laws and its cosmopolitan culture on the old world of the Mediterranean, and Romanised Christianity, so the federated democracy of the United States will prove to exist the guiding model for the next political phase of humanity'.

Slavery

Tocqueville was much less sanguine virtually the fledgling American republic. Many of his observations were both astute and prescient, for example apropos the grave political trouble of slavery. Tocqueville was perhaps the commencement author to show at length why modern representative republic could not live with slavery, every bit classical assembly-based democracy had managed to practice, admittedly with some discomfort. He highlighted how the 'calamity' of slavery had resulted in a terrible sub-division of social and political life. Black people in America were neither in nor of ceremonious society. They were objects of gross incivility. Legal and informal penalties against racial intermarriage were astringent. In those states where slavery had been abolished, black people who dared to vote, or to serve on juries, were threatened with murder. In that location was segregation and deep inequality in education. 'In the theatres gold cannot procure a seat for the servile race beside their sometime masters; in the hospitals they lie autonomously; and although they are immune to invoke the same God as the whites, it must be at a different altar and in their own churches, with their own clergy.' Prejudice even haunted the dead. 'When the Negro dies, his bones are cast bated, and the distinction of status prevails even in the equality of death.'

Lurking inside these racist customs was a disturbing paradox, Tocqueville observed. The prejudice directed at blackness people, he noted, increases in proportion to their formal emancipation. Slavery in America was in this sense much worse than in ancient Greece, where the emancipation of slaves for war machine purposes was encouraged by the fact that their skin colour was often the same every bit that of their masters. Both within and outside the institutions of American slavery, past contrast, blacks were made to suffer terrible bigotry, 'the prejudice of the primary, the prejudice of the race, and the prejudice of color', a prejudice that drew strength from simulated talk of the 'natural' superiority of whites. Such bigotry cast a long shadow over the future of American democracy, to the betoken where it now seemed to exist faced not only with the equally unpalatable options of retaining slavery or organised bigotry, only too with the outbreak of 'the well-nigh horrible of civil wars'. Tocqueville's political forecast was understandably gloomy: 'Attacked by Christianity equally unjust and by political economic system equally prejudicial, and now contrasted with autonomous liberty and the intelligence of our age, slavery cannot survive. By the human action of the master, or by the will of the slave, it volition end; and in either case great calamities may exist expected to ensue. If liberty be refused to the Negroes of the South, they volition in the end forcibly seize it for themselves; if information technology be given, they volition long abuse it.'

Tocqueville's white-skinned suspicion of black people should be noted, as should his accurate spotting of the poisonous contradiction betwixt slavery and the spirit of modern representative democracy. He was correct besides to be anxious about the magnitude of the trouble. By 1820, at to the lowest degree ten 1000000 African slaves had arrived in the New World. Some 400,000 had settled in North America, just their numbers had multiplied chop-chop, to the point where all united states south of the Mason-Dixon line were slave societies, in the full sense of the term. Even in New England, where there were comparatively few slaves, the economy was rooted in the slave trade with the West Indies. Every bit David Brion Davis has pointed out (in Challenging the Boundaries of Slavery), Afro-Americans did the difficult and dirty piece of work of the democratic republic. They cleared forests, turned the soil, planted and tendered and harvested the exportable crops that brought not bad prosperity to the slave-owning classes. So successful was the arrangement of slavery that after 1819 Southern politicians and landowners and their supporters inside the federal government agitated for its universal adoption. As a mode of production, and as a whole mode of life, slavery went on the warpath, as Abraham Lincoln fabricated clear in his non inaccurate claim that Slave Power was hell-bent on taking over the whole land, North as well as South.

The aggressiveness of Slave Power during the 1820s and 1830s disturbed the dreams of some Americans; it forced them to conclude that the American polity required a re-founding. Reasoning with their democratic hearts, they spotted that slavery was incompatible with the ethics of free and equal citizenship. These same opponents of slavery were to some degree aware of a contradiction that lurked within the contradiction. The problem, simply put, was whether or not the abolitionism of slavery could be done democratically, that is, past peaceful means such as petitioning and decisions past Congress, or whether war machine force would exist needed to defeat slavery's defenders.

In the cease, as we know, armed force decided, bringing with information technology iv years of terrible misery. An ugly struggle between two huge armies that locked horns ten,000 times, the Civil State of war was the get-go recorded war between 2 aspiring representative democracies, whose political elites were decumbent to think of themselves as defenders of 2 incompatible definitions of democracy. The conflict was in a way a disharmonism betwixt two different historical eras. The military machine burdensome of the Southern fantasy of Greek republic, in the name of a God-given vision of representative democracy, proved costly. Death, disability and destitution ruined hundreds of thousands of households, on both sides. At that place were an estimated 970,000 casualties, 3 per cent of the total population of the The states. Some 620,000 soldiers died, two-thirds from neglect and illness.

Despotism

Perhaps the most profound intuition of _Democracy in America _has to exercise with the long-term problem of despotism in the age of democracy. The complex story it tells arguably remains highly relevant for our times.

Tocqueville was acutely aware of the dangers posed by the rise, from within the middle of the new civil gild, of capitalist manufacturing industry and a new social power group (an 'aristocracy', he called them) of industrial manufacturers, whose power of control over uppercase threatens the freedom and pluralism and equality so essential for republic. (In Democracy in America Tocqueville does not consider workers equally a split social class merely rather as a menial fragment of la class industrielle. Here Tocqueville stood against Marx and sided with such contemporaries as Saint-Simon, for whom workers and entrepreneurs comprised a single social class: les industriels. This partly explains why Tocqueville later reacted in contradictory ways to the events of 1848; as François Furet and others have pointed out, he interpreted these events both as a continuation of the autonomous revolution and, rather spitefully, every bit a 'most terrible civil war' threatening the very basis of 'property, family unit and culture'.) This new 'aristocracy' applied the sectionalisation of labour principle to manufacturing, he noted. This dramatically increased the efficiency and volume of production, but at a loftier social toll. The modern organisation of industrial manufacturing, he claimed, creates a manufacturing class, comprising a stratum of workers, who are crowded into towns and cities, where they are reduced to mind-numbing poverty, and a stratum of center course owners, who love money and take no taste for the virtues of citizenship.

Tocqueville was among the first political writers to spot that a heart class gripped past selfish individualism and live-for-today materialism was prone to political promiscuity. A class of so-called citizens 'constantly circling for fiddling pleasures' could easily be persuaded to sacrifice their freedoms by embracing an 'immense protective power' that treats its subjects as 'perpetual children', as a 'flock of timid animals' in need of a shepherd. Confronting Aristotle ('a government which is composed of the center course more about approximates to democracy than to oligarchy, and is the safest of the imperfect forms of government'), Tocqueville argued that in fact the center class accept no automatic affinity with power-sharing democracy. Francis Fukuyama has said recently that 'the existence of a broad middle class' is 'extremely helpful' in sustaining 'liberal democracy'. But what Tocqueville long agone pointed out is that under democratic conditions, especially when the poor grow uppity, the eye grade might well brandish symptoms of what might exist called political neurasthenia: lassitude, aching fatigue and general irritability almost social and political disorder. Guided by fear and greed and professional and family honour and respectability, they would exist happy to be co-opted or kidnapped by land rulers, willing to be bought off with lavish services and cash payments and invisible benefits that brought them stable comforts.

With good reason, looking into the future, Tocqueville worried not just about the decline of public spirit within this middle class. Yes, he was especially exercised past its tendency to pursue wealth for the sake of wealth. That is why he worried his head about such bad 'habits of the heart' as cupidity and selfishness, possessive individualism and narrow-minded cunning. Just his worries ran deeper than this. Unlike Marx, Tocqueville predicted that both fractions of the new manufacturing course would press for regime support of their interests, for case through large-scale infrastructure projects, such equally the provision of roads, railways, harbours and canals. They would regard such projects necessary for the accumulation of wealth, the nurturing of equality and the maintenance of social order. When done in the name of the sovereign people, equally Tocqueville expected it would, authorities intervention and meddling in the affairs of civil society would choke the spirit of civil association. It might well lead, Tocqueville argued, to a new form of state servitude, the likes of which the world had never before seen.

The indicate is sketched in the fourth volume of Democracy in America, in 'What Blazon of Despotism Autonomous Nations Have to Fear?' 'I think the blazon of oppression threatening autonomous peoples is unlike annihilation always known', he wrote. Dissimilar past despotisms, which employed the coarse instruments of fetters and executioners, this new 'democratic' despotism would nurture administrative power that is 'absolute, differentiated, regular, provident and mild'. Peacefully, bit by bit, by ways of democratically formulated laws, government would morph into a new course of tutelary ability defended to securing the welfare of its citizens - at the loftier price of clogging the arteries of ceremonious society, thus robbing citizens of their collective power to act.

Tocqueville was sure that the fundamental problem of modern democracy was not the frantic and feverish mob, every bit critics of democracy from the fourth dimension of Plato had previously supposed. Modern despotism posed an entirely new and unfamiliar claiming. Feeding upon the fetish of private material consumption and the public apathy of citizens no longer much interested in politics, despotism is a new type of popular domination: a class of impersonal centralised power that masters the arts of voluntary servitude, a new type of state that is at once benevolent, mild and all-embracing, a disciplinary power that treats its citizens as subjects, wins their support and robs them of their wish to participate in government, or to pay attention to the mutual expert.

The thesis was certainly assuming, and original. Tocqueville was the starting time modern political writer to encounter and to say that a new form of despotism born of the dysfunctions of modern representative republic might well be our fate. He taught us that in the age of democracy forms of total power can only win legitimacy and govern effectively when they harness the trimmings and trappings of commonwealth – when they mirror and mimic actually-existing democracies, in order better to get beyond them. When we look back at the long crunch that gripped democracies a century after Tocqueville wrote, wasn't the totalitarianism of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia and Politician's Cambodia marked past more than a few autonomous features in this sense? And when we expect today at the new despotisms of the Eurasian region, Russia and Communist china for instance, shouldn't we ask whether these regimes are simulacra of Western democracies now bogged down in various dysfunctions and pathologies? Don't they make us wonder where our own so-called democracies are heading? Might they be signals of the emerging fact, unless something gives, that despotism is once again fated to play middle phase of our political lives in the coming years of the 21st century? Do nosotros non accept to give thanks Alexis de Tocqueville for warning us that they may well be the future of commonwealth?

petersonfeercer40.blogspot.com

Source: https://theconversation.com/why-read-tocquevilles-democracy-in-america-40802

0 Response to "What Parts of Democracy in America to Read"

Post a Comment